Romancing the Mystery: how stargazing helps with anxiety.

On why I adore telescopes, cosmic insignificance therapy, and sky porn.

I’ve always had a thing for telescopes.

I distinctly remember my first planetarium. It was a primary school excursion in the 80s. Back when space was still all galactic romantic - more Starwars than Starlink.

We reclined under domed projections of heavenly bodies as a Flight of the Navigator-esque narrator explained the nuances of the Milky Way:

“Our spiral galaxy is 100,000 light-years wide.

And just one light year equals nine and half trillion kilometres (that’s 12 zeros, kids).

Meaning it would take 1.9 billion earth years to cross it, if we could ever travel fast enough.”

We toured mini dioramas of the solar system in dimly lit corridors and learnt the planets names, chanting ‘My Very Excellent Mother Just Served Us Nine Pies’.

My obsession with the sky was born.

In my late teens I got into astrology, but unsatisfied with the WHY of it all, turned full tilt to astronomy by my 20s. I rawdogged quantum physics books (for dummies, mind you) and devoured every space doco DVD in Video Ezy.

There is something deeply soothing for the human existential quandary to contemplate the stars. Homosapiens have been doing it ever since we grew eyes and the capacity for curiosity.

Cosmic Insignificance Therapy.

A term coined by Oliver Burkman in his book 4000 Weeks. It describes the sense of feeling so tiny in the grand scheme of things that you loosen the grip on your own self importance.

This wide view can be a source of solace. Maybe that shopping list doesn’t look so important anymore. Or stacking the dishwasher properly pales in relevance. Holding this perspective is a key practice in Buddhist meditation. When your sense of self gets looser, your view of the world expands. And this creates a feeling of interconnectedness with the big everything.

In psychological fields, they call it ‘self-diminishment’. And it’s been shown to help recovery from PTSD, to increase prosocial behaviour (being more generous and cooperative), and making people more humble, as deemed by their friends.

Lately, I’ve been leaning into this astronomical salve even further. I seek out any chance for stargazing and keep a little astrophotography around the house, just to maintain the view.

A fave vintage print called, “The November Meteors: As observed between midnight and 5 o’clock AM, on the Night of November 13-14. 1868.”

Last year I went to Griffith Observatory in LA, my dream stopover en route to a meditation retreat. Unbeknownst to me, I stumbled into their monthly Public Star Party. A night for telescope enthusiasts to gather on the lawns and look up together. Friggen jackpot.

I wandered wide-eyed through the planetarium, lined up for a moon view through their telescope, and bought a magic star mug from the gift shop.

It might have been my exhilarating aloneness amidst the sprawling LA sunset, or the collective energy of so many budding astronomers, or a heavy-handed dose of Californian gummies… either way that night is immortalised in my personal history.

Cosmic Insignificance Therapy could be abbreviated as Awe - the subject of much contemporary research. A 2018 white paper by The University of California’s Greater Good Science Center found that awe experiences are linked with a reduction in rumination, depression, and chronic inflammation. A 2021 study argued that experiencing awe leads to self-transcendence, and may even expand our perception of time. Story checks out.

Awe is about coming into contact with a sense of vastness.

Dacher Keltner, a leading researcher in the psychology of awe, describes it as “The feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your current understanding of the world.” But vastness isn’t just about scale. It can be ideas, or music, or spiderwebs, or patterns of light on water.

Just a few weeks ago, I was in the desert on Andyamathna Country in Arkaroola. A certified dark sky reserve and home to some of the oldest fossils on earth. The perfect place for stargazing and geology porn.

One night, we booked a ‘Sky Explorer Session’ (you had me at hello) involving two hours with digital imagery from the million dollar array of telescopes they keep there.

Our guide, the village receptionist, and assumedly an undercover agent for NASA, pointed the enormous lens at Orion’s Belt. Just below the stars Sirius and Betelgeuse is the Orion Nebula. A stellar nursery that births baby suns, the lovechildren of collapsing gas and dust just 1,500 light-years from Earth.

Secret NASA guy explained,

“A ‘light year’ is a unit of distance, not time.

Because the stars we can see are thousands of light years away, it takes millions of our earth years for their starlight to travel through space and into your retinas.

So when you look at the stars, you’re essentially seeing back in time.”

Zoomed out like this, you can see us all here, ensconced in the momentary glory of our anthropocene. In homosapien’s flash of stardom on this 4 billion year old planet. A few centuries into our current civilisation’s rise and fall.

And if you look closely, there’s you: a body of congealed stardust roaming the crust of the earth alongside your fellow carbon-based organisms. Just here for a mere 4000 weeks or so.

Don’t feel lonely.

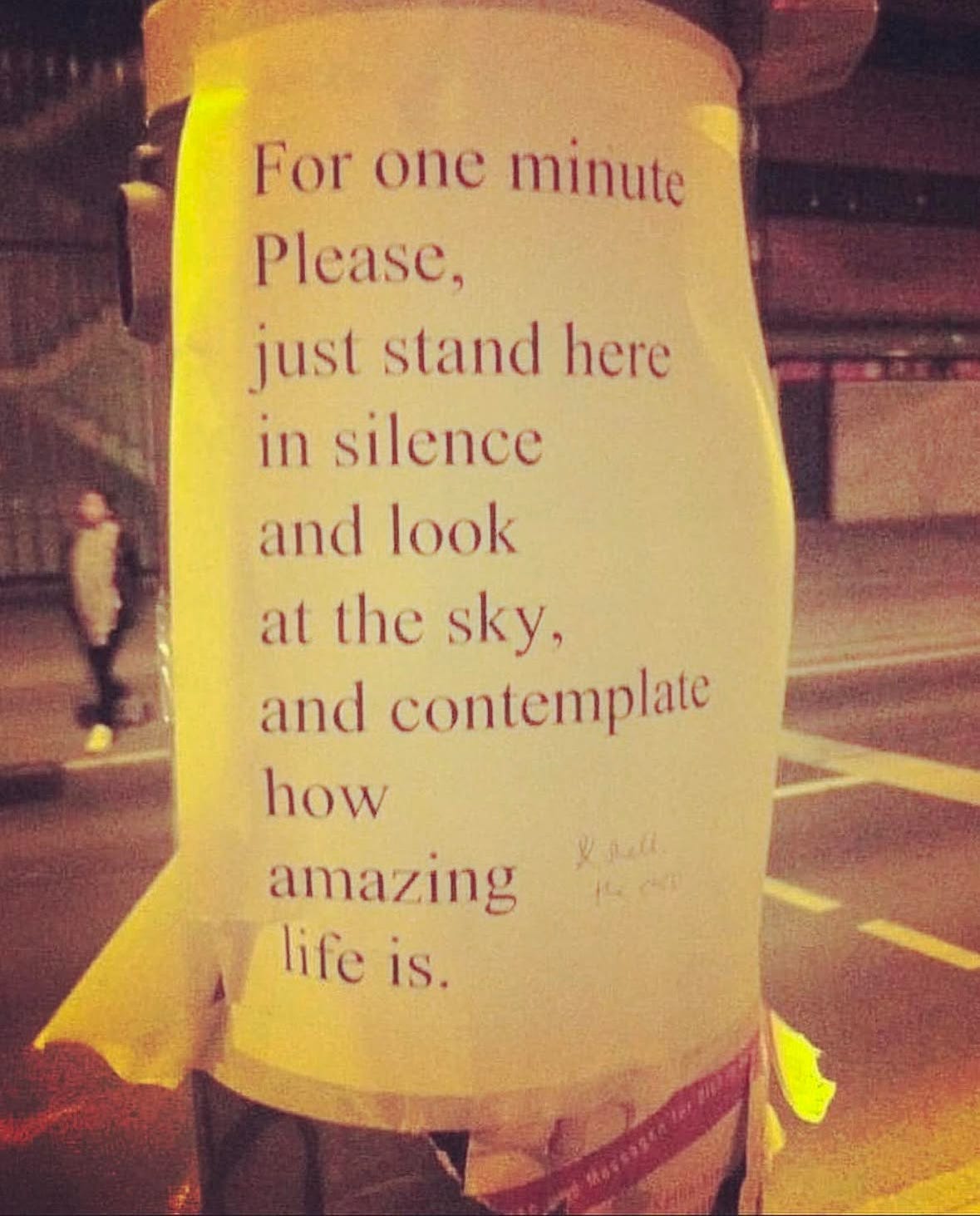

Looking up is an antidote to anxiety. Self-referential thinking (navel-gazing) leads to a contraction of identity and ultimately, disconnection. When our sense of self gets tighter we start desperately clinging to control all the details and the emails and the groceries, which feel increasingly urgent and important.

When we contact vastness, we open back up to the mysteries of life and to others. This is what I call romancing the mystery.

Please don’t confuse this with apathy. Despite the scale of it all, your tiny presence matters. Because you still make an impact on the world around you.

This is the wondrous paradox.

Your fleeting aliveness here matters because you are woven into the web of existence with all the other humans and mammals and reptiles and rivers and rainclouds.

Because you, and all of this, might be unrepeatable.

And while you’re here, there are beautiful things to do.

Awe provides relief from the existential quandary of being so temporarily alive in an infinitely expanding universe. So you can get on with living in it.

Stargazing helps us hold the paradox. To remember the unknowable mystery, and the groceries.

Life is strange that way.

So here’s your prescription: when you feel stuck in the details, or the dishwasher, or your self, go outside and look up. Better yet, go find a telescope.

Big love,

Tessa